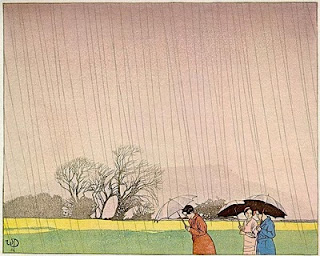

My dear printmaking colleagues, there are times when you discover a rare treat, and such is the case of Canada’s son Walter Joseph Phillips. I embrace the lyricism of this man’s work and admire greatly his ability to bring light and breath to an inked up piece of paper. Truly, these images sing with life and profess Phillip’s love of his adopted homeland. There is much to see and immerse oneself into his landscapes. They are simultaneously subtle and vibrant, but one feels in his prints the rapture of a sunset or a gentle rain. I hope you enjoy these pieces and share them with your colleagues. They are worth a good, long look…..

Walter Joseph Phillips was an English-born, Canadian artist. He was born in 1884 in Barton-on-Humber, Lincolnshire, England. He first studied art at the Birmingham School of Art, then went to study art in South Africa and Paris. He eventually went to work as a commercial artist in Manchester and London, then from 1908 to 1911 served as art master at the Bishop Woodworth School in Salisbury, England.

In 1913, he and his wife, Gladys(Pitcher), emigrated to Winnipeg, Manitoba, where they lived for nearly thirty years. From 1915-18 he began to produce small prints and during the summers he taught art at University of Wisconsin.

During the Great Depression he was one of a handful of artists who made a living off of his work. During 1925-1935 his subject matter mainly dealt with life on the Canadian prairies Manitoba and Northwest Ontario, but in the mid 1940s he switched to making images of the Rocky Mountains.(He asked that his ashes be spread over the Rocky mountains because he loved them so.)

In 1940 he was asked to become Artist in residence at the Banff School of Fine Arts. He moved to Calgary the next year and taught art at the Institute of Technology & Art. In the late 1950s his eyesight began to fail, and he moved to Victoria in 1960 where he dies three years later at the age of 78.

Phillips is famous for his Japanese-style woodcuts. His work was not considered avant garde. In fact, far from it. He was sensitive to his environment and portrayed it with a gentle and poetic vision. There is a calm and peaceful feeling when one looks at his work. His work exemplified the British influence which prevailed in Western Canada at that time. Yet, the Japanese printmaking influence of the 1800s is present with his compositions and a reverence of natural environs, but moreso, a feeling of the work of James McNeill Whistler is deeply felt. The mood is delicately handled. His places are dreamy, sweet and quiet. One can feel at peace in this work, and you can understand how one is drawn to the light as it caresses the land, the trees and water. Phillips has given us city-dwellers, and those unfamiliar with the beauty of Canada, a taste for its tranquility, its majesty.

Permanent Collections:

National Gallery of Canada

The Winnipeg Art Gallery

Glenbow Museum – have an extensive collection and a research archive

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies

Vancouver Art Gallery

The Pavilion Gallery in Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Park – have the most extensive collection, The Crabb Collection, comprising nearly 850 pieces.

His work was also collected in London, Washington D.C., New Jersey and Japan.

He was also a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

A place for talking about art, social issues, and most anything else I think THAT'S INKED UP.

Saturday, March 29, 2014

Saturday, March 15, 2014

The Linear Madness of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Portraits

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner b. Aschaffenburg, Bavaria,1880. d. Frauenkirch, Switzerland, 1938.

As a major player in the German Expressionist group Die Brucke, Kirchner ‘s work, particularly his prints, set new standards to express emotion and use of material. His fractured portraits were as equally jarring psychologically as much as how they were created. Kirchner sought everywhere for psychological understanding of his figures. His achievements are substantial.

These were the product of a man who had experienced pain and suffering, after having a nervous breakdown during his military service in WWI. It was a lifelong scar which he see-sawed between rising from and sinking into despair. Not surprisingly, the last straw was the condemnation of his life’s work from the Nazi party in 1933 when over 600 of his pieces were removed from museums and collections. They were mostly destroyed or sold, and 25 pieces were ‘selected’ for the infamous Degenerate art Exhibition of 1937. The ‘degenerate’ brand mortally wounded his numerous accomplishments and he never really recovered from the social stigma it produced. He couldn’t find work, and his former friends and colleagues abandoned him.

”… the reason why we founded the Brücke was to encourage truly German art, made in Germany. And now it is supposed to be un-German. Dear God. It does upset me".

Biography

Kirchner’s family were of Prussian origins and his mother was claimed to have descended from the Huguenots. Kirchner's family moved frequently so he attended schools in Frankfurt and Perlen until his father became Professor of Paper Sciences at the college of technology in Chemnitz. Kirchner's parents encouraged his artistic career but they also encouraged a pragmatic education so he moved to Dresden in 1901 to study architecture at the Königliche Technische Hochschule. Kirchner continued his studies in Munich 1903–1904, then he returned to Dresden in 1905 to complete his degree.

In 1905, Kirchner, along two other architecture students, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Erich Heckel, formed an artists’ group called Die Brücke ("The Bridge"). This group wanted to find a new method of artistic expression, bridging the past and the present. They looked to previous artists like Albrecht Dürer, Matthias Grünewald and Lucas Cranach the Elder, and they revived the medium of relief printmaking. From this point on, Kirchner committed himself to making art. The Die Brucke group had a major impact on the evolution of modern art in the 20th century and created what is called Expressionism. Kirchner composed a manifesto stating that "Anyone who directly and honestly reproduces that force which impels him to create belongs to us." Between 1907 and 1911, Kirchner spent summers with fellow Brucke arists at the Moritzburg lakes and on the island of Fehmarn. In 1911, he moved to Berlin, where he founded a private art school, MIUM-Institut, with Max Pechstein. It closed the following year, (but he also began a relationship with Erna Schilling which lasted the rest of his life.) In 1913, his writing of Chronik der Brücke led to the group’s demise.

At the beginning of WWI, Kirchner volunteered for military service. He was sent to Halle an der Saale to train as a driver. Kirchner's supervisor soon arranged for Kirchner to be discharged after he had a mental breakdown. (He struggled for the next few years to make art and bounced from one sanatorium to another.) Kirchner then returned to Berlin and continued to make art until 1915 when he was admitted to a sanatorium in Königstein in Taunus. During 1916, he returned to Berlin but he suffered another nervous breakdown and was admitted to a sanatorium in Berlin, Charlottenburg. Then, Kirchner was admitted to The Bellevue Sanatorium, in Kreuzlingen where he continued to produce paintings and woodcuts. In 1918, he was given a residence permit and he moved to "In den Lärchen" in Frauenkirch. Kirchner’s health eventually improved, and he made art and exhibited a lot in 1920 although he was still dependent on morphine.

He also began creating designs for carpets in 1921 which were then woven by Lise Gujer.

In 1925, Kirchner became close friends with fellow artist, Albert Müller and his family. He joined Rot-Blau, a new art group based in Basel, formed by Hermann Scherer, Albert Müller, Paul Camenisch and Hans Schiess, (but he left the group in 1929). At the end of 1925, Kirchner returned to Germany, visiting Frankfurt, Chemnitz, and Berlin. In 1926, Kirchner's close friend, Albert Müller, died and the next year, Kirchner organized a memorial exhibition for him at the Kunsthalle Basel.

In 1930, Kirchner began to experience health problems from smoking and during 1936 and 1937, his health further declined, suffering from a semi-paralysis in his hands. Towards the end of his life Kirchner became increasingly afraid after Austria was annexed by Germany, and he feared Germany might also invade Switzerland. In the summer of 1938, Kirchner took his own life. He was later buried in the Waldfriedhof cemetery.

The tragedy this artist suffered was one among many whose lives were torn apart during the world wars. German society as a whole was the most educated, one of the most elite societies in Europe of the time. Germany’s decimation; the loss of its teachers, writers, philosophers, musicians, artists, dancers, etc., etc. was nearly complete. The artists who fled Germany survived, but the ones who remained, those who believed and supported the Nazi party were cruelly and completely humiliated by the masses. They became isolated and many, like Kirchner, couldn’t endure it.

In closing, this artist’s pure, raw emotions are present on every one of his portraits; in every deeply gouged line, on every single block. Their faces will eternally cry out about incomprehensible injustices and hang precariously on the edge of madness. We can internalize their suffering. These works remind us what it is to be human, what it is to want to be compassionate.

One would hope the world’s current politicos would look a little more often at the powerful and important work produced by this artist and the group he is associated with. They have seen and shown us the ‘other side’, the ‘evil side’ of humanity. Do we ever need experience again situations like those that influenced this work?

Some of Kirchner’s Exhibitions and Accomplishments:

1906 first Die Brucke exhibition, K.F.M. Seifert and Co., Dresden, Germany

1913 Armory Show, NY

1913 first major solo show, Essen Folkwang Museum

1920 several exhibitions in Germany and Switzerland

1921 major display of Kirchner's work in Berlin

1931 made a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, but resigned in 1933

1933 his work was branded as "degenerate" by the Nazis and 639 works were taken out of museums, destroyed or sold.

1934, Kirchner visited Berne and Zurich, and met Paul Klee.

1935 Kirchner created a sculpture for a new school in Frauenkirch, Switzerland.

1937 25 pieces exhibited in the Degenerate Art Exhibition, sponsored by Hitler’s Nazi party

1937 first solo museum show in the US, Detroit Institute of Arts, MI

1937 organizes Muller memorial exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland

1969 a major retrospective at the Seattle Art Museum, the Pasadena Art Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

1992 the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

2006 Christie's auction of Kirchner's Street Scene, Berlin (1913) = a record $38 million.

2008 Museum of Modern Art, NY

As a major player in the German Expressionist group Die Brucke, Kirchner ‘s work, particularly his prints, set new standards to express emotion and use of material. His fractured portraits were as equally jarring psychologically as much as how they were created. Kirchner sought everywhere for psychological understanding of his figures. His achievements are substantial.

These were the product of a man who had experienced pain and suffering, after having a nervous breakdown during his military service in WWI. It was a lifelong scar which he see-sawed between rising from and sinking into despair. Not surprisingly, the last straw was the condemnation of his life’s work from the Nazi party in 1933 when over 600 of his pieces were removed from museums and collections. They were mostly destroyed or sold, and 25 pieces were ‘selected’ for the infamous Degenerate art Exhibition of 1937. The ‘degenerate’ brand mortally wounded his numerous accomplishments and he never really recovered from the social stigma it produced. He couldn’t find work, and his former friends and colleagues abandoned him.

”… the reason why we founded the Brücke was to encourage truly German art, made in Germany. And now it is supposed to be un-German. Dear God. It does upset me".

Biography

Kirchner’s family were of Prussian origins and his mother was claimed to have descended from the Huguenots. Kirchner's family moved frequently so he attended schools in Frankfurt and Perlen until his father became Professor of Paper Sciences at the college of technology in Chemnitz. Kirchner's parents encouraged his artistic career but they also encouraged a pragmatic education so he moved to Dresden in 1901 to study architecture at the Königliche Technische Hochschule. Kirchner continued his studies in Munich 1903–1904, then he returned to Dresden in 1905 to complete his degree.

In 1905, Kirchner, along two other architecture students, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Erich Heckel, formed an artists’ group called Die Brücke ("The Bridge"). This group wanted to find a new method of artistic expression, bridging the past and the present. They looked to previous artists like Albrecht Dürer, Matthias Grünewald and Lucas Cranach the Elder, and they revived the medium of relief printmaking. From this point on, Kirchner committed himself to making art. The Die Brucke group had a major impact on the evolution of modern art in the 20th century and created what is called Expressionism. Kirchner composed a manifesto stating that "Anyone who directly and honestly reproduces that force which impels him to create belongs to us." Between 1907 and 1911, Kirchner spent summers with fellow Brucke arists at the Moritzburg lakes and on the island of Fehmarn. In 1911, he moved to Berlin, where he founded a private art school, MIUM-Institut, with Max Pechstein. It closed the following year, (but he also began a relationship with Erna Schilling which lasted the rest of his life.) In 1913, his writing of Chronik der Brücke led to the group’s demise.

At the beginning of WWI, Kirchner volunteered for military service. He was sent to Halle an der Saale to train as a driver. Kirchner's supervisor soon arranged for Kirchner to be discharged after he had a mental breakdown. (He struggled for the next few years to make art and bounced from one sanatorium to another.) Kirchner then returned to Berlin and continued to make art until 1915 when he was admitted to a sanatorium in Königstein in Taunus. During 1916, he returned to Berlin but he suffered another nervous breakdown and was admitted to a sanatorium in Berlin, Charlottenburg. Then, Kirchner was admitted to The Bellevue Sanatorium, in Kreuzlingen where he continued to produce paintings and woodcuts. In 1918, he was given a residence permit and he moved to "In den Lärchen" in Frauenkirch. Kirchner’s health eventually improved, and he made art and exhibited a lot in 1920 although he was still dependent on morphine.

He also began creating designs for carpets in 1921 which were then woven by Lise Gujer.

In 1925, Kirchner became close friends with fellow artist, Albert Müller and his family. He joined Rot-Blau, a new art group based in Basel, formed by Hermann Scherer, Albert Müller, Paul Camenisch and Hans Schiess, (but he left the group in 1929). At the end of 1925, Kirchner returned to Germany, visiting Frankfurt, Chemnitz, and Berlin. In 1926, Kirchner's close friend, Albert Müller, died and the next year, Kirchner organized a memorial exhibition for him at the Kunsthalle Basel.

In 1930, Kirchner began to experience health problems from smoking and during 1936 and 1937, his health further declined, suffering from a semi-paralysis in his hands. Towards the end of his life Kirchner became increasingly afraid after Austria was annexed by Germany, and he feared Germany might also invade Switzerland. In the summer of 1938, Kirchner took his own life. He was later buried in the Waldfriedhof cemetery.

The tragedy this artist suffered was one among many whose lives were torn apart during the world wars. German society as a whole was the most educated, one of the most elite societies in Europe of the time. Germany’s decimation; the loss of its teachers, writers, philosophers, musicians, artists, dancers, etc., etc. was nearly complete. The artists who fled Germany survived, but the ones who remained, those who believed and supported the Nazi party were cruelly and completely humiliated by the masses. They became isolated and many, like Kirchner, couldn’t endure it.

In closing, this artist’s pure, raw emotions are present on every one of his portraits; in every deeply gouged line, on every single block. Their faces will eternally cry out about incomprehensible injustices and hang precariously on the edge of madness. We can internalize their suffering. These works remind us what it is to be human, what it is to want to be compassionate.

One would hope the world’s current politicos would look a little more often at the powerful and important work produced by this artist and the group he is associated with. They have seen and shown us the ‘other side’, the ‘evil side’ of humanity. Do we ever need experience again situations like those that influenced this work?

Some of Kirchner’s Exhibitions and Accomplishments:

1906 first Die Brucke exhibition, K.F.M. Seifert and Co., Dresden, Germany

1913 Armory Show, NY

1913 first major solo show, Essen Folkwang Museum

1920 several exhibitions in Germany and Switzerland

1921 major display of Kirchner's work in Berlin

1931 made a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, but resigned in 1933

1933 his work was branded as "degenerate" by the Nazis and 639 works were taken out of museums, destroyed or sold.

1934, Kirchner visited Berne and Zurich, and met Paul Klee.

1935 Kirchner created a sculpture for a new school in Frauenkirch, Switzerland.

1937 25 pieces exhibited in the Degenerate Art Exhibition, sponsored by Hitler’s Nazi party

1937 first solo museum show in the US, Detroit Institute of Arts, MI

1937 organizes Muller memorial exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland

1969 a major retrospective at the Seattle Art Museum, the Pasadena Art Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

1992 the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

2006 Christie's auction of Kirchner's Street Scene, Berlin (1913) = a record $38 million.

2008 Museum of Modern Art, NY

Monday, March 10, 2014

Sybil Andrews: Prints in HyperDrive!

Sybil Andrews (1898 –1992) was a British-Canadian printmaker best known for her modernist prints. She has become known for her multi-colored images which break with printmaking traditions. Her compositions gyrate and flip the viewer back and forth like riding a Brahma bull. Shapes and figures are used to help propel the viewer through her compositions much in the same way Cezanne does, only Andrews’ compositions have us on an unending whirly-gig or carousel and we can’t quite figure out where to get off.

Andrews’ works also reflect her society’s growing interest in the modern age, its concern with speed and with technological developments. She chose to portray rhythms of life with the human figure, through images of urban travel and sporting events.

Born in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, England, Andrews was the third of five children born to Charles and Beatrice Andrews. After completing her high school education, Andrews wanted to study art, but her family couldn’t afford to send her to college. She went and apprenticed as a welder in an airplane factory during WWI, taking art correspondence courses on the side. When the war ended, she returned to her hometown and took up teaching at the Portland House School.

In 1922, Andrews moved to London to attend the Heatherley’s School of Fine Arts. She later took a secretarial position at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art to help pay for more classes. It was there she learned about printmaking. Her first subjects were the farming working class from her hometown, depicting agricultural life and sporting activities.

During WWII, she returned to welding warships. There she met her future husband, Walter Morgan, and in 1947 they got married and moved to Campbell River, British Columbia. Here she achieved a large following which lasted well into the 1950’s. Her work was rediscovered in the 1970’s and she enjoyed a growing and appreciative audience. She died in 1992 leaving a body of nearly 80 prints.

England has a large collection of her work at St. Edmundsbury Borough Council Heritage Service, Bury St Edmunds. This collection includes a number of early pieces produced while she lived in Suffolk. The Glenbow Museum has a major collection (over 1000 works) of Andrews' art, including all her prints, original blocks, sketchbooks, and personal archives.

Honors:

Andrews was elected to the Society of Canadian Painters, Etchers and Engravers in 1951. In 1975 she completed The Banner of St Edmund - a hand embroidered silk on linen, begun in 1930. It is found in the Treasury of St James Cathedral, in Bury St. Edmunds, the town of her birth.

Public Collections:

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

The Bank of New York Mellon Collection, USA (Private Collection)

British Museum, London, UK

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, USA

Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Canada

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Moyse's Hall Museum, Suffolk, UK

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, New Zealand

Virtual Museum of Canada

This bit of news was sent from fellow inkster Laura Widmer after my initial post…..Sybil Andrews published a book titled "Artist's Kitchen" ISBN: 0 9512047 0 X. It was first published in

the UK in 1985 by RK Hudson with 2nd and 3rd runs in 1990 and 1992

respectively. It is a gem of a book of no-nonsense advice to

artists...sometimes amusing, sometimes harsh, but most often true. On the

title page it reads:

"This is the Kitchen where the ingredients of the cakes and pastries are

being assembled. It is NOT the display counter. It is a meditation on the

When, the How, the Where and the Why of Art and Artists."

Andrews compiled it from her years of private teaching and while it can be

tricky to find, it is well worth the search. The Campbell River Arts Council may still have a few copies of Andrews’ book available for sale. They discovered a box of books in 2009 and they sell them as a fundraising item(See attached newsletter).

http://www.crarts.ca

Andrews’ works also reflect her society’s growing interest in the modern age, its concern with speed and with technological developments. She chose to portray rhythms of life with the human figure, through images of urban travel and sporting events.

Born in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, England, Andrews was the third of five children born to Charles and Beatrice Andrews. After completing her high school education, Andrews wanted to study art, but her family couldn’t afford to send her to college. She went and apprenticed as a welder in an airplane factory during WWI, taking art correspondence courses on the side. When the war ended, she returned to her hometown and took up teaching at the Portland House School.

In 1922, Andrews moved to London to attend the Heatherley’s School of Fine Arts. She later took a secretarial position at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art to help pay for more classes. It was there she learned about printmaking. Her first subjects were the farming working class from her hometown, depicting agricultural life and sporting activities.

During WWII, she returned to welding warships. There she met her future husband, Walter Morgan, and in 1947 they got married and moved to Campbell River, British Columbia. Here she achieved a large following which lasted well into the 1950’s. Her work was rediscovered in the 1970’s and she enjoyed a growing and appreciative audience. She died in 1992 leaving a body of nearly 80 prints.

England has a large collection of her work at St. Edmundsbury Borough Council Heritage Service, Bury St Edmunds. This collection includes a number of early pieces produced while she lived in Suffolk. The Glenbow Museum has a major collection (over 1000 works) of Andrews' art, including all her prints, original blocks, sketchbooks, and personal archives.

Honors:

Andrews was elected to the Society of Canadian Painters, Etchers and Engravers in 1951. In 1975 she completed The Banner of St Edmund - a hand embroidered silk on linen, begun in 1930. It is found in the Treasury of St James Cathedral, in Bury St. Edmunds, the town of her birth.

Public Collections:

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

The Bank of New York Mellon Collection, USA (Private Collection)

British Museum, London, UK

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, USA

Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Canada

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Moyse's Hall Museum, Suffolk, UK

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, New Zealand

Virtual Museum of Canada

This bit of news was sent from fellow inkster Laura Widmer after my initial post…..Sybil Andrews published a book titled "Artist's Kitchen" ISBN: 0 9512047 0 X. It was first published in

the UK in 1985 by RK Hudson with 2nd and 3rd runs in 1990 and 1992

respectively. It is a gem of a book of no-nonsense advice to

artists...sometimes amusing, sometimes harsh, but most often true. On the

title page it reads:

"This is the Kitchen where the ingredients of the cakes and pastries are

being assembled. It is NOT the display counter. It is a meditation on the

When, the How, the Where and the Why of Art and Artists."

Andrews compiled it from her years of private teaching and while it can be

tricky to find, it is well worth the search. The Campbell River Arts Council may still have a few copies of Andrews’ book available for sale. They discovered a box of books in 2009 and they sell them as a fundraising item(See attached newsletter).

http://www.crarts.ca

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)