In thinking about all things spring, I came upon the botanical prints of Tanigami Konan of Japan. His floral prints drew my attention immediately for their brilliant rich color and simplicity of composition. The thing is, though, they did not remind me of any botanical print I have ever seen before. There is something non-Asian about them. The compositions feel more influenced by western ideals than Asian, and in fact, they are.

The work is wonderfully simple in execution and as we might find in Asian works, there is little or nothing to distract us from the subject. The subject is all there is to see, and as a viewer, we cannot want for more. What is portrayed is perfect. Konan’s delicate lines and carefully composed blooms lets the viewer smell them and imagine walking amongst them in a garden of our own making.

Admirers and collectors of traditional botanical prints will find them refreshingly pungent in color, less concerned with scientific detail, although they are quite accurately described. The issue here is not to separate the viewer from the image- to analyze it – but to immerse the viewer with the subject. Konan succeeds in this goal superbly.

Tanigami Konan was born 1879 in Hyogo, Japan. He was a well-known artist of the Kacho-e Nihon-ga (birds and flowers) tradition, and he was the first Japanese artist to portray Western flowers. Konan produced five portfolios of prints called 'Seiyo Soka Zofu', (A Picture Album of Western Plants and Flowers), which were published in 1917/18. They were organized as a visual record of flowers, depicting them in full bloom. Four portfolios were devoted to the spring and summer flowers, and the last portfolio combined autumn/winter flowers and plants.

These prints display the very best flowers - tulips, lilies, daffodils, crocus, and iris of the botanical world. Their appeal was driven by the compositionally fuller style of the West versus the East’s more restrained version.

Konan is especially known for his peony series. (Peonies are one of my favorite flowers.) He was selected to create a series of twenty-four prints for the Teiten (Imperial Exhibition of 1917).

These prints were printed in a large format. Their bold, bright colors are stunning, and they are considered some of the finest floral images ever printed.

The choice to publish these prints was done at a very interesting time in Japan’s printmaking history; when older, traditional ways of printing were yielding to new western technologies.

Artists and printers in Japan were losing their living due to these modern developments, so they chose to pursue subjects that would appeal to Western collectors. Heavily influenced by the French Impressionist movement, they incorporated Western concepts of light, shade and perspective.

This new movement was called Shin Hanga or “new prints”, and it was an immediate success in early 20th-century Japan, during the Taishō and Shōwa periods. Shin Hanga subjects are vastly appealing: botanicals, landscapes, birds, animals and beautiful people.

It maintained the traditional ukiyo-e collaborative system (hanmoto system) where the artist, carver, printer, and publisher engaged in division of labor. The movement grew from 1915 to 1942, then halted briefly during World War II. The American occupation renewed interest in prints and many were sent home by the American troops.

Still as popular as ever, botanical print collectors would do well to add some of Konan's beauties to their collections. Enjoy, my inked up friends, and partake of a little stroll through Konan’s garden of delights.

A place for talking about art, social issues, and most anything else I think THAT'S INKED UP.

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

Monday, May 16, 2016

The Japonisme Prints of Bertha Lum

Bertha Boynton Bull Lum (1869 – 1954) was born in Tipton, Iowa. She studied briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago. Around this time there were several exhibitions which popularized Japanese art and culture in America, including the Chicago World's Fair of 1893. She became enamored of the Japonisme movement and wanted to go visit Japan to study art.

In 1903, she married and honeymooned in Japan. She returned to the US and made several woodblock prints which clearly show the influence of both French impressionism and ukiyo-e. Lum made subsequent trips to Japan in 1907 and 1911, primarily to learn more about Japanese printmaking. She was able to study carving in the workshop of Bonkotsu Igami.

Later on she decided to hire carvers and printers to work under her since she came to realize that the Japanese system of collaborative printmaking was more efficient for her purposes. Her prints were featured in the 1912 Tenth Annual Art Exhibit in Ueno Park where she was the only Western artist included. Lum soon exhibited her work in Chicago and New York.

She moved to Peking, China in 1922, but returned to the United States in 1924 to live in California. She published two books, Gods, Goblins and Ghosts in 1922 and Gangplanks to the East in 1936. She left California in 1927, then returned to Peking in 1933. She continued to show her work in the United States and China until 1950. In 1953 she moved to Genoa, Italy, where died in 1954.

Lum's prints combine flowing, curvillinear Art-Nouveau lines with flat colorful sections that harken back to 19th century ukiyo-e. The subject of her work ranges from children to landscapes to mysterious figures from Asian folklore and legend. Lum envisioned Asia as an exotic, magical place full of lantern light, swirling smoke, and smiling women.

Stylistically, Lum's work is delicately printed with colorful light and shadowy clouds. Her figures fade into the atmosphere, giving the compositions a dramatic depth. Her work became influenced by the author Lafcadio Hearn, who translated Japanese legends and fairy tales into popular Western books. Ultimately, Lum’s work made a significant contribution to the Japonisme movement with her prints and paintings.

Awards

Silver medal at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition

Her work received honors in Rome, Paris and Portugal

Membership

Asiatic Society of Japan

California Society of Etchers (now the California Society of Printmakers)

Print Makers Society of California

Portrait of Bertha Lum.

In 1903, she married and honeymooned in Japan. She returned to the US and made several woodblock prints which clearly show the influence of both French impressionism and ukiyo-e. Lum made subsequent trips to Japan in 1907 and 1911, primarily to learn more about Japanese printmaking. She was able to study carving in the workshop of Bonkotsu Igami.

Later on she decided to hire carvers and printers to work under her since she came to realize that the Japanese system of collaborative printmaking was more efficient for her purposes. Her prints were featured in the 1912 Tenth Annual Art Exhibit in Ueno Park where she was the only Western artist included. Lum soon exhibited her work in Chicago and New York.

She moved to Peking, China in 1922, but returned to the United States in 1924 to live in California. She published two books, Gods, Goblins and Ghosts in 1922 and Gangplanks to the East in 1936. She left California in 1927, then returned to Peking in 1933. She continued to show her work in the United States and China until 1950. In 1953 she moved to Genoa, Italy, where died in 1954.

Lum's prints combine flowing, curvillinear Art-Nouveau lines with flat colorful sections that harken back to 19th century ukiyo-e. The subject of her work ranges from children to landscapes to mysterious figures from Asian folklore and legend. Lum envisioned Asia as an exotic, magical place full of lantern light, swirling smoke, and smiling women.

Stylistically, Lum's work is delicately printed with colorful light and shadowy clouds. Her figures fade into the atmosphere, giving the compositions a dramatic depth. Her work became influenced by the author Lafcadio Hearn, who translated Japanese legends and fairy tales into popular Western books. Ultimately, Lum’s work made a significant contribution to the Japonisme movement with her prints and paintings.

Awards

Silver medal at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition

Her work received honors in Rome, Paris and Portugal

Membership

Asiatic Society of Japan

California Society of Etchers (now the California Society of Printmakers)

Print Makers Society of California

Portrait of Bertha Lum.

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

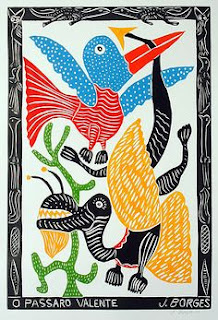

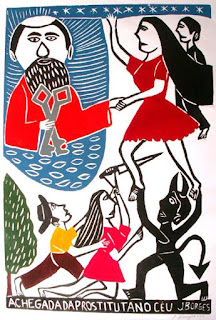

Jose Francisco Borges' Prints on the Life and Culture of Brazil

José Francisco Borges was born in 1935 in Bezerros, Brazil. He is Latin America’s best-known folk artist working in relief, and his work has been exhibited all over the world. He comes out of a long tradition of folk poet/artists who publish their own work in the form of small inexpensive chap-books written in verse, known as folhetos or literatura de cordel, because vendors sell them in the marketplace, hanging over a string.

The backcountry of Brazil is as big as the state of Texas, and it is filled with cowboys, bandits, simple folk and a strong sense of faith. The people from this area are descended from the Portuguese, and they have come to enjoy hearing story-telling poems set to song. These poems are sung by traveling minstrels who spread local gossip as they move from town to town. Frequently, vendors sing these songs to market crowds, many of whom are illiterate, and their voices usually draw enormous gatherings.

Brazilian chap books deal with popular poetry, accounts of local catastrophes, popular legends, famous crimes, and infamous love affairs. The front of these pamphlets usually contain simple, eye-catching illustrations of the book's contents, and they have become a special type of folk art.

Borges worked as a child in the remote fields of north-east Brazil. In his 20s, he started trading, making and illustrating books of popular poems, which lead him from Brazil’s backlands to exhibitions at some of the most prestigious art museums in the world. When Borges wrote and illustrated his first book, he sold 5,000 copies in two months! He has created over 250.

In the 1960s, Borges began writing folhetos, and soon also began to operate a printing press to produce woodcut prints for their covers. He then started producing folio-sized prints from their woodcuts, transforming them into an art form by themselves.

His bold, naive compositions, inspired by politics and folklore, are prized by collectors and shown in exhibitions around the world. Borges received a UNESCO cultural award in 2000. Borges still lives and works in Bezerros. He retains a plain view of his inspiration, saying: “I carve what I see.”

Borges work is simple, colorful and exudes a felling of childlike wonder. His images of two-timing women, marriage and fighting the temptations of the Devil are all done in a playful manner, easy for the viewer to digest.

Many galleries handle Borges' work, and you can easily find them online for a song. No pun intended. Snap some up, my dear inked up comrades, as we must support our brethren.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)