During his career, he visited the United sattes, the Soviet Union, and several Latin American countries as a guest lecturer and visiting artist. His prints are stellar examples of mass and volume and expressive abstraction. Their capacity to evoke passion and anger are beyond the world's sometimes limited scope of understanding of printmakers and the work they do. His background as a painter helped keep his original prints from Looking like prints, thus making them unique compared with his colleagues.

Born in Chihuahua, but

growing up in Guanajuato, many details

of Siqueiros’ childhood were confusing, in part because he gave misleading information

regarding his life. What is known is that Siqueiros was the second of three

children. His father, Cipriano Alfaro, was well-off, and his mother, Teresa

Siqueiros, watched after their children: David, his sister, Luz, and his brother

"Chucho" (Jesús). When Siqueiros was four years old, his father sent

the children to be raised by their paternal grandparents after his mother had died.

The main part of Siqueiros’ life was spent between making his art and his interest in politics. Schooling aside, the opportunity to network with fellow students for political debate and marches and protests was a larger part of his educational experience. While in school, he came across the writings of Dr. Atl, who in 1906 published a manifesto calling for Mexican artists to look toward their ancestral roots to develop a national Mexican art style. This inspired the young artist to become active in politics. At the age of fifteen, Siqueiros was involved in a student strike at the Academy of San Carlos of the National Academy of Fine Arts, which eventually established of an “open-air academy”. Three years later, he and several of his friends from the School of Fine Arts joined Carranza’s Constitutional Army. In 1914, Siqueiros became interested in the army’s “post-revolutionary” infighting. He traveled throughout Mexico during his military service and saw the difficult conditions of his country’s poor working class. It instilled in him a lifelong passion to speak for the masses with his art and his political activities.

In 1919, he went to Paris and

learned about Cubism, the work of Paul Cezanne and there he met Rivera, with

whom he traveled to Italy to study the work of the Renaissance fresco painters.

During this period, Siqueiros' artistic and political activities had become conjoined

and by 1921 he wrote a manifesto

in Vida Americana, called

"A New Direction for the New Generation of American Painters and

Sculptors." He called for a "spiritual renewal" to bring back classical

painting while infusing "new values" about the “modern machine” and

the “contemporary aspects of daily life". Through this style, Siqueiros

hoped to create a bridge between a national and universal art.

In 1922, Siqueiros returned to Mexico City work for the government with fellow artists Rivera and José Orozco painting murals in several prominent buildings. In 1923 Siqueiros helped found the Syndicate of Revolutionary

Mexican Painters, Sculptors and Engravers, which addressed the problem of

widespread public access through its union paper, El Machete, the weekly paper that became the official

mouthpiece for the country's Communist Party.

Siqueiros remained deeply

involved in union labor activities, as well as the Mexican Communist Party,

until he was jailed and eventually exiled in the early 1930s for his political connections. Siqueiros

produced a series of politically themed lithographs during this period, which were exhibited in

the United States. His lithograph Head was shown at the 1930 exhibition

“Mexican Artists and Artists of the Mexican School” at The Delphic Studios in

New York City. Siqueiros also worked in Los Angeles, where his

murals there told the story of America's forceful relationship with Latin

America. Siqueiros’s work was honored at

the XXV Venice Biennale in the first ever Mexican exhibition with Orozco, Rivera and Rudolfo Tamayo in 1950,

which recognized the international status of Mexican art.

Siqueiros was involved with the Communist Party who in 1940 unsuccessfully tried to assassinate Leon Trotsky. In 1960, he was unjustly arrested for openly attacking the President of Mexico and protesting the arrests of striking workers and teachers. While imprisoned Siqueiros continued to paint, and

his works continued to sell.

He later settled in Cuernavaca

where he lived until his death in 1974.

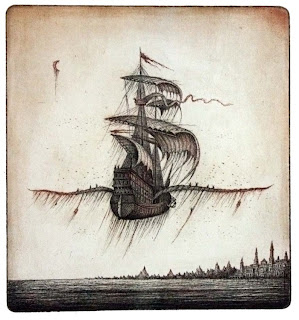

Most of this man's printmaking efforts were composed of strong figures, and the later colorful works, moved toward abstraction and abstracted brushwork that didn't look like his contemporaries. They are in fact quite curious pieces and call to mind spiritual musing upon his own travails and the seemingly bi-polar nature of his career path. I find the subtlety of his prints color, the massive weight of his self-portraits and the political bent of his action figures a reasonable and persuasive argument for his diverse subjects. In all, they relate closely to his painting style, and the somewhat chopped off compositions which remind me of El Greco's paintings of earthly and heavenly realms simultaneously depicted. There is also an element of Francisco Goya's Disasters of War prints with his butchered figures. Siqueiros butchers the body of Christ, showing his suffering, floating his body between the earth and heaven.

Some people don't get those weirdly surreal images, but no matter. Siqueiros' work was consistent showing us the suffering of humanity, the suffering of the poor and the suffering of an artist as all artists suffer to bring forth their view of the world. His world wasn't a calm or happy place, but it was real, and it still speaks volumes for present-day Mexico's suffering masses about the societal and political woes that have befallen that poor abandoned country.

Some people don't get those weirdly surreal images, but no matter. Siqueiros' work was consistent showing us the suffering of humanity, the suffering of the poor and the suffering of an artist as all artists suffer to bring forth their view of the world. His world wasn't a calm or happy place, but it was real, and it still speaks volumes for present-day Mexico's suffering masses about the societal and political woes that have befallen that poor abandoned country.