Sending holiday wishes to everyone this season. I hope your time with family and friends and sharing time with the occasional stranger proves fruitful and creates happy memories. Instead of my usual story or historical article about printmaking, this year I just wanted to post some excellent prints about the birth of Christ and the nativity. As you will see there are many artists who have made images on the subject. You will notice I am posting some prints that are much older than the usual timeline I write about. I thought it would be a nice diversion to show some works by older printmakers this round.

At this time of year we all can all spend a little time away from the office, or studio and spend some time with those people that mean something to us. I wish everyone a blessed holiday, and will see you in the new year!

A place for talking about art, social issues, and most anything else I think THAT'S INKED UP.

Monday, December 25, 2017

Monday, December 4, 2017

Joyous Nature as Seen by Colin See-Paynton

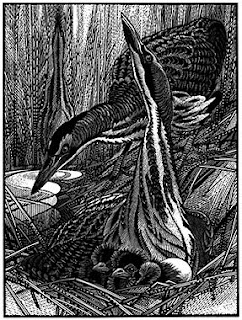

An owl seeks its prey under stealth of night under a moonlit sky....A hawk surveys its domain on its lofty perch....A mother and father protect their young hatchlings....All this and more is seen through the wonder-filled eyes of Colin See-Paynton.

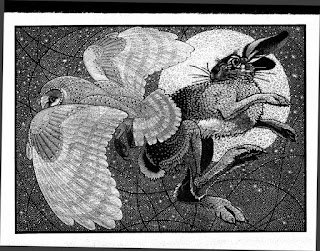

See-Paynton is a self-taught printmaker (who lives in Wales) whose love of nature is reflected in animals that nest, birds that fly and rabbits that scurry underbrush in the night. His delightful portrayal of these creatures is not merely descriptive, but also fanciful. There is a story waiting to be told in each of his prints. The loving care with which he describes these animals, and the sometimes playful manner in which they cross each other's paths is charming and curious. I want to know more about the rabbit that crosses the owl like they are both going lickity-split, faster than light, and suddenly find themselves nearly missing running into each other. The confusion on the face of the rabbit says it all, like "Hey man, slow down! I am supposed to be the fastest thing running around here."

Similarly, the fox and the owl are racing toward their prey as they jump over a slip of a moon, with the celestial stars to illuminate their way. There is a race going on to be sure, but they seem more intent to race and beat each other, rather than catch a little bite to eat.

See-Paynton captivates his audience with his subject, but also the mythical places in which they dwell. There is a sort of no man's land his subjects run and fly through, but if we allowed ourselves to wander into a wood, I am sure we would see and hear the same subjects flit by our feet and swoop by our heads. See-Paynton shows us a quieter place and time, where the rush to get to work or the hassles of a day-to-day job fade away as we contemplate the lightning speed of a hawk as it chases its prey, or the hear the quiet ripples of water in a brook as ducks look under the surface of the water to see the catfish meandering below.

See-Paynton clearly loves his work, and the images are beautifully crafted with a deft precision and variety of line. His is a world full of wonder and observance of the laws of nature. Hopefully, we can all spend a little time out in the less traveled world and delight in what we discover.

Memberships:

1983 Associate of the Royal Society of Painter Etchers and Engravers

1984 Member of the Society of Wood Engravers

1986 Fellow of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers

1993 Fellow of the Royal Cambrian Academy

Public Collections:

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Belfast City Art Gallery, Belfast, Ireland

Berlin Graphothek, Berlin, Germany

Central Museum & Art Gallery, Northampton

Freemantle Museum & Art Gallery, Australia

Guangdong Museum of Art, China

Museum of Modern Art, Wales

National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, Wales

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, Wales

Swansea Museum & Art Gallery

Victoria & Albert Museum, London, England

See-Paynton is a self-taught printmaker (who lives in Wales) whose love of nature is reflected in animals that nest, birds that fly and rabbits that scurry underbrush in the night. His delightful portrayal of these creatures is not merely descriptive, but also fanciful. There is a story waiting to be told in each of his prints. The loving care with which he describes these animals, and the sometimes playful manner in which they cross each other's paths is charming and curious. I want to know more about the rabbit that crosses the owl like they are both going lickity-split, faster than light, and suddenly find themselves nearly missing running into each other. The confusion on the face of the rabbit says it all, like "Hey man, slow down! I am supposed to be the fastest thing running around here."

Similarly, the fox and the owl are racing toward their prey as they jump over a slip of a moon, with the celestial stars to illuminate their way. There is a race going on to be sure, but they seem more intent to race and beat each other, rather than catch a little bite to eat.

See-Paynton captivates his audience with his subject, but also the mythical places in which they dwell. There is a sort of no man's land his subjects run and fly through, but if we allowed ourselves to wander into a wood, I am sure we would see and hear the same subjects flit by our feet and swoop by our heads. See-Paynton shows us a quieter place and time, where the rush to get to work or the hassles of a day-to-day job fade away as we contemplate the lightning speed of a hawk as it chases its prey, or the hear the quiet ripples of water in a brook as ducks look under the surface of the water to see the catfish meandering below.

See-Paynton clearly loves his work, and the images are beautifully crafted with a deft precision and variety of line. His is a world full of wonder and observance of the laws of nature. Hopefully, we can all spend a little time out in the less traveled world and delight in what we discover.

Memberships:

1983 Associate of the Royal Society of Painter Etchers and Engravers

1984 Member of the Society of Wood Engravers

1986 Fellow of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers

1993 Fellow of the Royal Cambrian Academy

Public Collections:

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Belfast City Art Gallery, Belfast, Ireland

Berlin Graphothek, Berlin, Germany

Central Museum & Art Gallery, Northampton

Freemantle Museum & Art Gallery, Australia

Guangdong Museum of Art, China

Museum of Modern Art, Wales

National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, Wales

National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, Wales

Swansea Museum & Art Gallery

Victoria & Albert Museum, London, England

Friday, November 17, 2017

Be Thankful This Holiday Season!

Although the American concept of Thanksgiving developed in the colonies of New England, its roots can be traced back to the other side of the Atlantic. Both the Separatists who came over on the Mayflower and the Puritans who arrived soon after brought with them a tradition of providential holidays—days of fasting during difficult or pivotal moments and days of feasting and celebration to thank God in times of plenty.

As an annual celebration of the harvest and its bounty, Thanksgiving falls under a category of festivals that spans cultures, continents and millennia. In ancient times, the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans feasted and paid tribute to their gods after the fall harvest. Thanksgiving also bears a resemblance to the ancient Jewish harvest festival of Sukkot. Historians have noted that Native Americans had a rich tradition of commemorating the fall harvest with feasting and merrymaking long before Europeans set foot on their shores.

For some scholars, the jury is still out on whether the feast at Plymouth really constituted the first Thanksgiving in the United States. Indeed, historians have recorded other ceremonies of thanks among European settlers in North America that predate the Pilgrims’ celebration.

In 1565, the Spanish explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilé invited members of the local Timucua tribe to a dinner in St. Augustine, Florida, after holding a mass to thank God for his crew’s safe arrival. On December 4, 1619, when 38 British settlers reached a site known as Berkeley Hundred on the banks of Virginia’s James River, they read a proclamation designating the date as “a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God.”

In 1621, the Plymouth colonists and Wampanoag Indians shared an autumn harvest feast that is acknowledged today as one of the first Thanksgiving celebrations in the colonies. For more than two centuries, days of thanksgiving were celebrated by individual colonies and states. It wasn’t until 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a national Thanksgiving Day to be held each November.

In September 1620, a small ship called the Mayflower left Plymouth, England, carrying 102 passengers—group of religious separatists seeking a place where they could freely practice their faith, plus other people lured by the promise of prosperity and land ownership in the New World. After a treacherous and uncomfortable crossing, they dropped anchor near the tip of Cape Cod. One month later, the Mayflower crossed Massachusetts Bay, and the Pilgrims began the work of establishing a village at Plymouth.

Throughout the first brutal winter, most of the colonists remained on board the ship, where they suffered from exposure, scurvy and outbreaks of contagious disease. Only half of the Mayflower’s original passengers and crew lived to see their first New England spring.

In March, the remaining settlers moved ashore, where they received an astonishing visit from an Abenaki Indian who greeted them in English. Several days later, he returned with Squanto, a member of the Pawtuxet tribe who had been kidnapped by an English sea captain and sold into slavery before escaping to London and returning to his homeland on an exploratory expedition. Squanto taught the Pilgrims, weakened by malnutrition and illness, how to cultivate corn, extract sap from maple trees, catch fish in the rivers and avoid poisonous plants. He also helped the settlers forge an alliance with the Wampanoag, a local tribe, which would endure for more than 50 years and tragically it remains one of the sole examples of harmony between the European colonists and Native Americans.

In November 1621, after the Pilgrims’ first corn harvest proved successful, Governor William Bradford organized a feast and invited a group of the Native American allies, including the Wampanoag chief Massasoit. Now remembered as American’s “first Thanksgiving” the festival lasted for three days. While no record exists of the banquet’s menu, the Pilgrim chronicler Edward Winslow wrote that Governor Bradford sent four men on a “fowling” mission in preparation for the event, and that the Wampanoag guests arrived bearing five deer. Because the Pilgrims had no oven and the Mayflower’s sugar supply had dwindled by the fall of 1621, the meal did not feature pies, cakes or other desserts, which have become a hallmark of contemporary celebrations.

Pilgrims held their second Thanksgiving celebration in 1623 to mark the end of a long drought that had threatened the year’s harvest and prompted Governor Bradford to call for a religious fast. Days of fasting and thanksgiving on an annual or occasional basis became common practice in other New England settlements as well.

During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress designated one or more days of thanksgiving a year, and in 1789 George Washington issued the first Thanksgiving proclamation by the national government of the United States; where he called upon Americans to express their gratitude for the happy conclusion to the country’s war of independence and the successful ratification of the U.S. Constitution. His successors John Adams and James Madison also designated days of thanks during their presidencies.

In 1817, New York became the first of several states to officially adopt an annual Thanksgiving holiday; however each state celebrated it on a different day. Abraham Lincoln finally in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, in a proclamation entreating all Americans to ask God to “commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife” and to “heal the wounds of the nation” scheduled Thanksgiving for the final Thursday in November, and it was celebrated on that day every year until 1939, when Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the holiday up a week in an attempt to spur retail sales during the Great Depression.

In many American households, the Thanksgiving celebration now centers on cooking and sharing a bountiful meal with family and friends. Turkey may or may not have been on the menu when the Pilgrims hosted the inaugural feast in 1621. Today, however, nearly 90 percent of Americans eat the bird on Thanksgiving. Other traditional foods include stuffing, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie. Volunteering is a common Thanksgiving Day activity, and communities often hold food drives and host free dinners for the less fortunate.

May you all have a great Thanksgiving holiday with your family, friends and those in need of company. Blessings to everyone!

Monday, October 23, 2017

Chizuko Yoshida's Balance of Nature

Chizuko Yoshida (née Inoue) was born in 1924 in Japan. She is a Modernist artist, whose work reflects the developments of Japanese art post World War II. She is also the middle link in the succession of three generations of women artists in the Yoshida family(a rarity in Japanese art). She is the wife of artist Hodaka Yoshida (1926–1995). Hodaka’s mother, Fujio Yoshida (1887–1987), was a noted artist alongside of her husband Hiroshi Yoshida (1876–1950). Chizuko's daughter, Ayomi Yoshida (born 1958), is well known for her modernist prints and installations.

Chizuko's first art teacher was Fumio Kitaoka. She studied design at Hongo Art Institute until it was destroyed in WWII. Due to the frequent air raids she was sent to Aoyama until the end of the war, then in 1949 joined an art seminar of Okamoto Tarō. A year later she became a member of two important art associations: the Pacific Painting Society, and Shuyōkai.

She joined two important art associations after returning to Tokyo: the Pacific Painting Society (Taiheiyō-Gakai), established in 1902 by Hiroshi Yoshida and Ishikawa Toraji and the Vermilion Leaf Society (Shuyōkai), a womens’ artist group, established by Fujio Yoshida (1887-1987)in 1920.

In the late 1940s, Chizuko started participating in a group of avant-garde artists, writers, and intellectuals called the Century Society (Seiki no kai), who met to discuss art theory and criticism. Okamoto Tarō, a prominent Surrealist painter and critic, led the group where Chizuko was exposed to discourse on the integration of Japanese cultural traditions with international modernist ideas. Under Okamoto’s influence, Chizuko's work moved toward abstract compositions.

She began submitting works to the Taiheiyō shows and in 1949 was made an associate member of the group. It was through the Taiheiyō that she met Hodaka Yoshida. They attended Onchi Kōshirō’s art seminar together, held an exhibition of their works and in 1953 they were married. They have two children, Ayomi and Takasuke (1959- an art jewelry maker), and they have had long careers as independently inspired modern printmakers.

Chizuko eventually developed her own distinctive style. In her best-known abstractions, she expresses the ephemeral beauty of nature: the balance one finds between delicacy and strength, and the variety within repetition. Her prints range from geometric abstraction to music to nature. Underlying her compositions is an inner strength, the recollection of a moment. Later, in the mid-1960s, she embraced a 3-dimensional quality to her work. Chizuko’s best-known subjects are butterflies.

Chizuko has been a member of the Japanese Print Association since 1954 and she also helped establish the Women’s Printmakers Association in 1954. She has exhibited in the College Women’s Association of Japan since 1956 and in the annual Contemporary Women’s Exhibition in Ueno Museum since 1987. She has been invited to exhibit in many international art and print biennials.

In 2014, she was one of five contemporary Japanese women artists featured in Portland Art Museum’s exhibition called “Breaking Barriers: Japanese Women Print Artists 1950–2000."

Public Collections:

The British Museum

Art Institute of Chicago

Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art

Tokyo International Museum of Modern Art

Yokohama Museum of Art

Chizuko's first art teacher was Fumio Kitaoka. She studied design at Hongo Art Institute until it was destroyed in WWII. Due to the frequent air raids she was sent to Aoyama until the end of the war, then in 1949 joined an art seminar of Okamoto Tarō. A year later she became a member of two important art associations: the Pacific Painting Society, and Shuyōkai.

She joined two important art associations after returning to Tokyo: the Pacific Painting Society (Taiheiyō-Gakai), established in 1902 by Hiroshi Yoshida and Ishikawa Toraji and the Vermilion Leaf Society (Shuyōkai), a womens’ artist group, established by Fujio Yoshida (1887-1987)in 1920.

In the late 1940s, Chizuko started participating in a group of avant-garde artists, writers, and intellectuals called the Century Society (Seiki no kai), who met to discuss art theory and criticism. Okamoto Tarō, a prominent Surrealist painter and critic, led the group where Chizuko was exposed to discourse on the integration of Japanese cultural traditions with international modernist ideas. Under Okamoto’s influence, Chizuko's work moved toward abstract compositions.

She began submitting works to the Taiheiyō shows and in 1949 was made an associate member of the group. It was through the Taiheiyō that she met Hodaka Yoshida. They attended Onchi Kōshirō’s art seminar together, held an exhibition of their works and in 1953 they were married. They have two children, Ayomi and Takasuke (1959- an art jewelry maker), and they have had long careers as independently inspired modern printmakers.

Chizuko eventually developed her own distinctive style. In her best-known abstractions, she expresses the ephemeral beauty of nature: the balance one finds between delicacy and strength, and the variety within repetition. Her prints range from geometric abstraction to music to nature. Underlying her compositions is an inner strength, the recollection of a moment. Later, in the mid-1960s, she embraced a 3-dimensional quality to her work. Chizuko’s best-known subjects are butterflies.

Chizuko has been a member of the Japanese Print Association since 1954 and she also helped establish the Women’s Printmakers Association in 1954. She has exhibited in the College Women’s Association of Japan since 1956 and in the annual Contemporary Women’s Exhibition in Ueno Museum since 1987. She has been invited to exhibit in many international art and print biennials.

In 2014, she was one of five contemporary Japanese women artists featured in Portland Art Museum’s exhibition called “Breaking Barriers: Japanese Women Print Artists 1950–2000."

Public Collections:

The British Museum

Art Institute of Chicago

Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art

Tokyo International Museum of Modern Art

Yokohama Museum of Art

Labels:

Chizuko Yoshida,

Japanese Modernist,

music,

woodblock prints

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)