One of Chicago’s most beloved printmakers, muralist and political activist Carlos Cortez (1923–2005) was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the son of a Mexican Indian Wobbly union organizer father and a German socialist pacifist mother. Starting in 1947, for sixty years, , Cortez was involved with the Industrial Workers of the World,writing articles and drawing cartoons for the union’s

newspaper. He identified himself as an anarcho-syndicalist, and was an accomplished artist

and a highly influential political artist. After

Cortez married in 1965, he and his wife moved to Chicago where he became an

integral part of the local Mexican and Chicano mural movement until his death.

Cortez is perhaps best known for his wood and linoleum-cut prints.

When linoleum became too expensive, he worked with woodblocks. “There’s a work of

art waiting to be liberated inside every chunk of wood. I’m paying homage to

the tree that was chopped down by making this piece of wood communicate

something.” --- C.Cortez

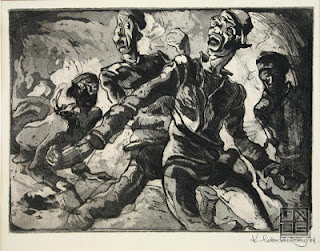

Inspired by the works of José Guadalupe Posada and Käthe Kollwitz, Carlos combined technical and stylistic influences from German Expressionism and themes from ancient Aztec and modern Chicano sources to make numerous prints about striking workers, miners, farm workers and portraits about labor organizers. More often, his art was about advocating for a position, rather than opposing some situation. His social sympathies are akin to the works of French artists Pissaro, Signac, and Millet, but he was often heard to credit Posada as his greatest influence. He also had affinities with the work of Siquieros and Leopoldo Mendez.

Inspired by the works of José Guadalupe Posada and Käthe Kollwitz, Carlos combined technical and stylistic influences from German Expressionism and themes from ancient Aztec and modern Chicano sources to make numerous prints about striking workers, miners, farm workers and portraits about labor organizers. More often, his art was about advocating for a position, rather than opposing some situation. His social sympathies are akin to the works of French artists Pissaro, Signac, and Millet, but he was often heard to credit Posada as his greatest influence. He also had affinities with the work of Siquieros and Leopoldo Mendez.

I once attended a panel discussion that included Cortez and some notable local artists and art historians. An exhibition of Cortez' prints surrounded the panel discussion. At one point in the discussion, an arrogant art historian (obviously trying to make an inflammatory statement to rile up the crowd) made a derogatory statement about Cortez' life's work for social reform. The audience gasped, and then people started to decry the historian for his lack of respect for Cortez and his work. The trick was in. The historian had deliberately played the 'insult card', but I sat back and watched Mr. Cortez during the audience's ensuing tirade. He was calm, collected, unfazed. He realized what the historian was up to, and wasn't about to lower himself or his work to respond. When it came time for him to speak he quietly, calmly, and with compassion, put the historian and his cheap grand-standing tactic in it's place. The audience cheered. Cortez knew his self-worth and his work would outlast some historian's cheap flashpoint of debate. You see, he knew - as most artists do - that his work will live on, and speak a truth that will be long felt after his passing. No one can take that away or demean its sincerity.

Chicago's National Museum of Mexican Art, which holds the largest, most complete collection of Carlos Cortez' work, has exhibited a complete installation of the artist’s living room studio. His work is otherwise found in several museum collections worldwide, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

As an artist for the masses, this final statement about keeping his art available for the public is in keeping with his generous nature, and making sure the message of his work stays in the public’s eye.I hope this will inspire other artists to share their work more with their unknown audience, since our messages must remain in the public's eye to be powerful and meaningful.

“… when you do a graphic, the amount of prints you can

make from it is infinite. I made a provision in my estate, for whoever will

take care of my blocks, that if any of my graphic works are selling for high

prices, immediate copies should be made to keep the price down.”

–Carlos Cortez

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)